The Mind Outside My Head: Tim Parks

"…Everything

we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell, Manzotti argues, involves the

same creation of a physical unity—the moment of consciousness—sustained

by processes within and without the head. The room, or part of a room,

that you see now, including the screen on which you’re reading this

blog, becomes, in combination with your faculties, a whole; this is

consciousness. It happens in time, and it takes time (consciousness of

visual phenomena seems to require at least 100 milliseconds to occur),

and it changes constantly…"

Peter Marlow/Magnum Photos

Lighthouse at Dungeness, coast of Kent, Great Britain, 2006

“There are no images.” This was the first time I noticed Riccardo Manzotti. It was a

conference on art and neuroscience.

Someone had spoken about the images we keep in our minds. Manzotti

seemed agitated. The girl sitting next to me explained that he built

robots, was a genius. “There are no images and no representations in our

minds,” he insisted. “Our visual experience of the world is a continuum

between see-er and seen united in a shared process of seeing.”

I

was curious, if only because, as a novelist I’d always supposed I was

dealing in images, imagery. This stuff might have implications. So we

had a beer together.

Manzotti has a degree in

engineering and another in philosophy. He teaches in the psychology

department at IULM University, Milan. The move from engineering to

philosophy was prompted by conceptual problems he’d run into when first

seeking to build robots. What does it mean that a subject sees an

object? “People say the robot stores images of the world through its

video camera. It doesn’t, it stores digital data. It has no images.”

Manzotti

is what they call a radical externalist: for him consciousness is not

safely confined within a brain whose neurons select and store

information received from a separate world, appropriating, segmenting,

and manipulating various forms of input. Instead, he offers a model he

calls Spread Mind: consciousness is a process shared between various

otherwise distinct processes which, for convenience’s sake we have

separated out and stabilized in the words

subject and

object. Language, or at least our modern language, thus encourages a false account of experience.

His

favorite example is the rainbow. For the rainbow experience to happen

we need sunshine, raindrops, and a spectator. It is not that the sun and

the raindrops cease to exist if there is no one there to see them.

Manzotti is not a Bishop Berkeley. But unless someone is present at a

particular point no colored arch can appear. The rainbow is hence a

process requiring various elements, one of which happens to be an

instrument of sense perception. It doesn’t exist whole and separate in

the world nor does it exist as an acquired image in the head separated

from what is perceived (the view held by the “internalists” who account

for the majority of neuroscientists); rather, consciousness is spread

between sunlight, raindrops, and visual cortex, creating a unique,

transitory new whole, the rainbow experience. Or again: the viewer

doesn’t see the world; he is part of a world process.

Everything

we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell, Manzotti argues, involves the

same creation of a physical unity—the moment of consciousness—sustained

by processes within and without the head. The room, or part of a room,

that you see now, including the screen on which you’re reading this

blog, becomes, in combination with your faculties, a whole; this is

consciousness. It happens in time, and it takes time (consciousness of

visual phenomena seems to require at least 100 milliseconds to occur),

and it changes constantly.

This minimal time lapse

(some claim it is as much as 500 milliseconds) required for brain and

world to generate consciousness allows Manzotti to deal with what would

seem to be the obvious objection to the externalist theory. Do we not

have consciousness when the eyes are shut and the mind lies in silence?

And what about dreams? Isn’t the brain evidently sufficient to sustain

consciousness without support from outside?

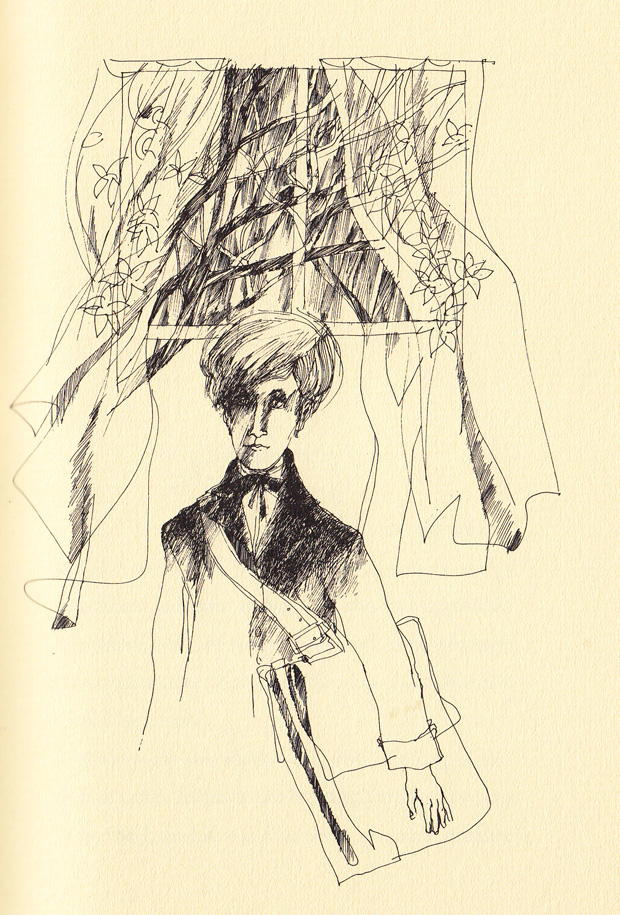

We do

indeed have consciousness in these moments, Manzotti replies, but it is

still spread out between mind and world. It may take only a fraction of a

second for you to become conscious of the face appearing at your

window, and then three more years before the same face surfaces in a

dream, perhaps mingled with all kinds of other stimuli from elsewhere.

But this doesn’t change the fact that consciousness is a coming together

of brain and world: the physical process begun at the window is

continuing in memory and dream. The congenitally blind, Manzotti points

out, don’t dream colors because they have never encountered them.

Consciousness is the mingling of mind process with the processes we call

objects that are all in a state of flux, however fast or slow.

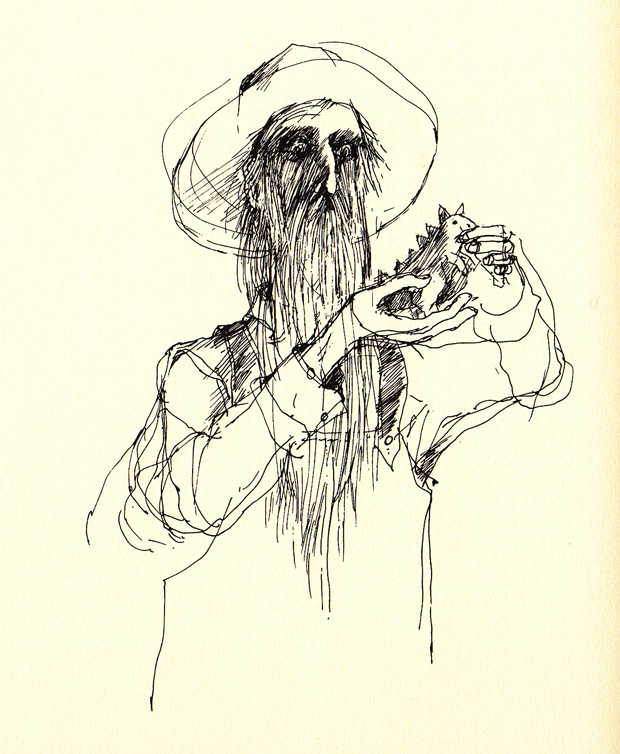

Gianni Ansaldi

Riccardo Manzotti

Let’s

leave aside the gospel truth or otherwise of all this. I tend to be

skeptical of people with big ideas and Manzotti, like Einstein I

suppose, has the long unkempt hair and animated manner of the possibly

crazy scientist or visionary. All the same, you can see at once that

taking his externalist ideas on board would radically change our

approach to the notion of what an individual or a self is. Which in

turn, for a novelist—and

that’s my job—means

a different way of thinking about narrative, about description, about

character. The fact is that I met Manzotti shortly after attending a

ten-day retreat where, in strict silence, people were trying to develop a

Buddhist meditation technique called Vipassana. I had gone originally

for

health reasons,

assured that the technique was useful for chronic pain and with no

intention at all (for heaven’s sake) of taking on board any ideas that

might be in the air. But the experience was so fascinating it was

impossible not to be curious.

“Are you aware,” I asked

Manzotti, “of the Buddhist principle of ‘conditioned arising,’ which

seems remarkably similar to your insistence that there are neither

objects nor subjects nor images, but only processes in a state of flux?”

Manzotti

is irritated by this digression. He isn’t aware of Buddhist ideas. Just

as he worries that people will confuse his determinedly “physical” view

of consciousness with Berkeley’s idealism, so he wants to avoid like

the plague being mixed up with anything that smells New Age.

“The

Buddha,” I rib him, “argued that the world was made up of

infinitesimally small particles in a constant cause-and-effect flux, and

in Vipassana the meditator is invited to contemplate that flux in his

own mind and body and to accept his oneness with it. Do it for ten days

in a row in complete silence and you begin to understand why Buddhists

don’t accept the existence of the self as a separate entity, or, if you

like, why Buddhist priests don’t write novels.”

Manzotti

reflects. He is a man who publishes academic papers constructed, as is

appropriate, with the most careful reasoning in the most respectable

journals and, to boot, designs charming comic-strip essays that

introduce non-professionals to his view of the world by analyzing such

things as what it means when we see a face, or hear a tune, or call a

thing an object.

Over a drink, however, he’ll go a little further:

If,

as I believe, the orthodox, internalist vision of consciousness is

false and even naive, then we have to ask why so many intelligent people

hold it. It’s not hard to understand. By locating consciousness

exclusively within the brain we can imagine that the subject, me, at

some very deep level, is not subject to the same law of constant change

that evidently governs the phenomena around me. The subject accrues and

sheds attributes, but remains in essence him or herself. This allows for

the notion of someone’s being responsible, even for actions carried out

years ago, and hence gives rise to a particular moral universe; it also

creates the comforting illusion that perhaps the self could survive

separate from the world. Behind it all there is the desire to deny

change in ourselves, perhaps to survive death. Anyway, to be an entity

outside the world.

I laugh: “If we’re going to claim

that society holds the vision it does because it’s comforting and

convenient, then why do you hold a different one?”

Manzotti

doesn’t answer the question directly. It’s time to order another beer.

“Notions of convenience might not be the same for everyone,” he

eventually ponders. “For example, a guy obsessed by building a robot

that simulates human behavior would have special reasons for wanting to

get the model of consciousness right.”

The Reasoner

A panel from

A process oriented externalist solution to the hard problem by Riccardo Manzotti

For

some time I walk the streets of Milan trying to accept that

consciousness is not locked in my head but spread out across the revving

traffic, the rustling leaves, the dog shit, the blue sky, the gritty

cobbles, the solemn facades, the soft breeze, the unseasonal

temperatures, the screaming children, the air, the women. After a while

it begins to make sense. There are small shifts of mood passing from

street to park, from outside to inside, from red to blue, male to

female, night to day, tram to metro, center to suburb. There are varying

tensions between focus of vision and field of vision, between

conversation and background noise. In general there is more: the

intrusion of smells, the slap of a passing truck, a persistent touching

of heat and breeze. Oddly, the critical faculty is somewhat attenuated;

one distinguishes a little less urgently between the beautiful and the

ugly, the slow line and the fast in bank and supermarket. Sometimes it’s

a tiny bit like reading a passage from Joyce, who was never a favorite

author of mine.

Not of course that Manzotti would ever

suggest that people should do this. He’s a scientist. Consciousness is

consciousness whatever your ideas about it. You don’t decide whether the

mind is spread, if spread it is. All the same, once you accept that

this might be a more accurate model of how things are, then oddly enough

things do begin to feel different. I guess we’re just that kind of

creature: within or without, consciousness can be profoundly altered by a

voice declaring, “There are no images.”

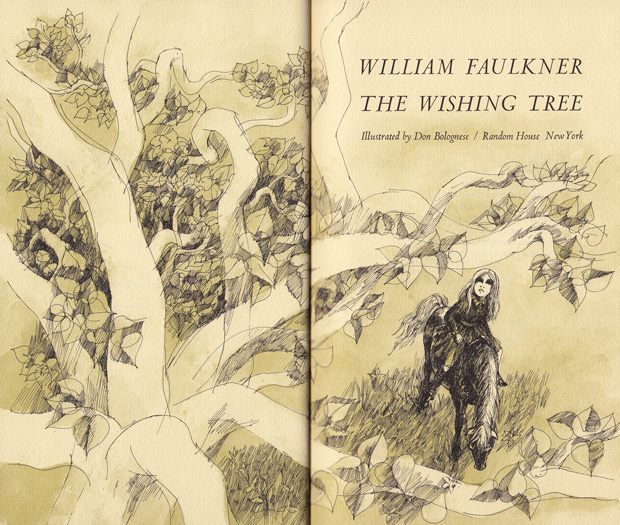

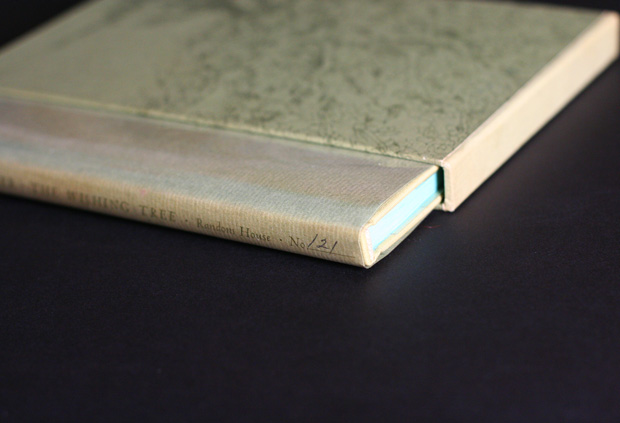

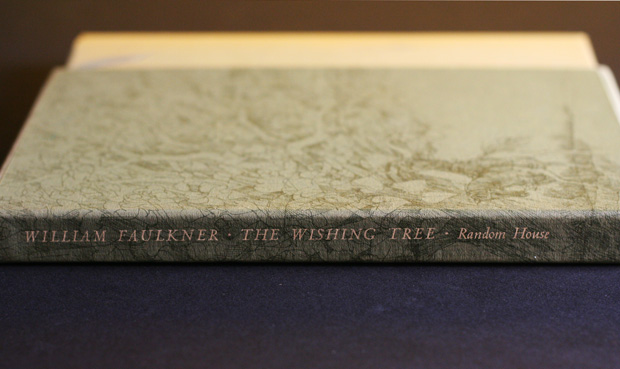

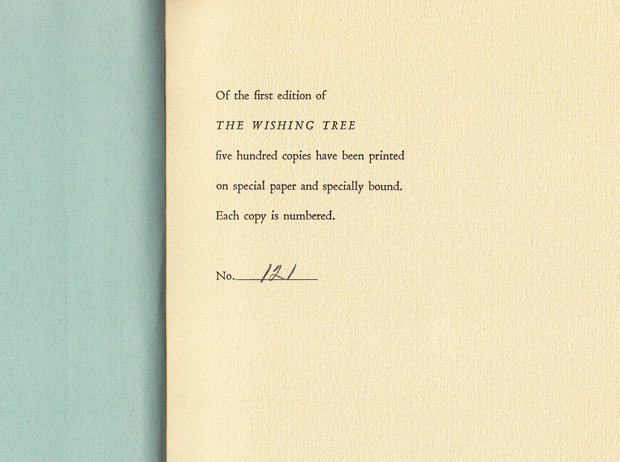

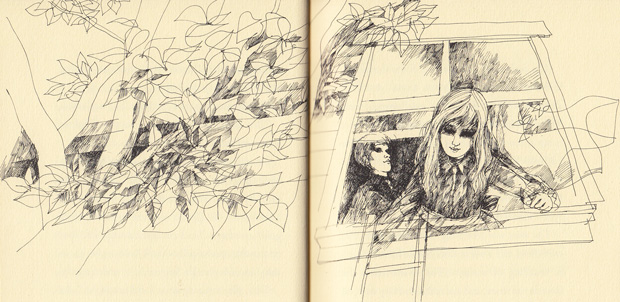

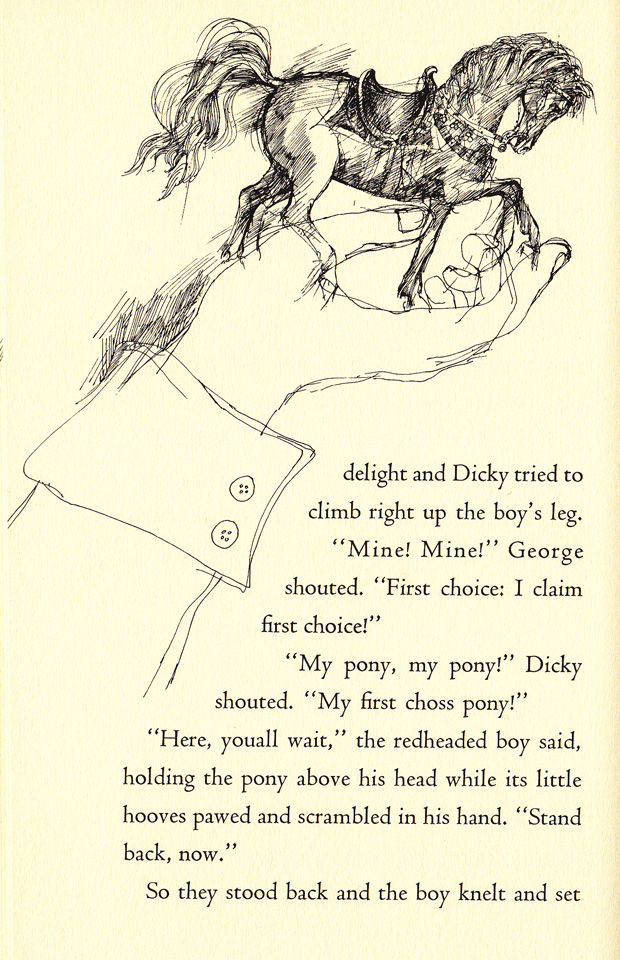

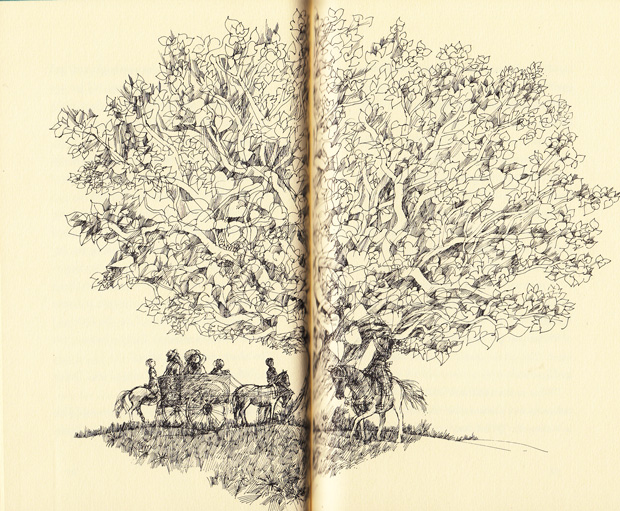

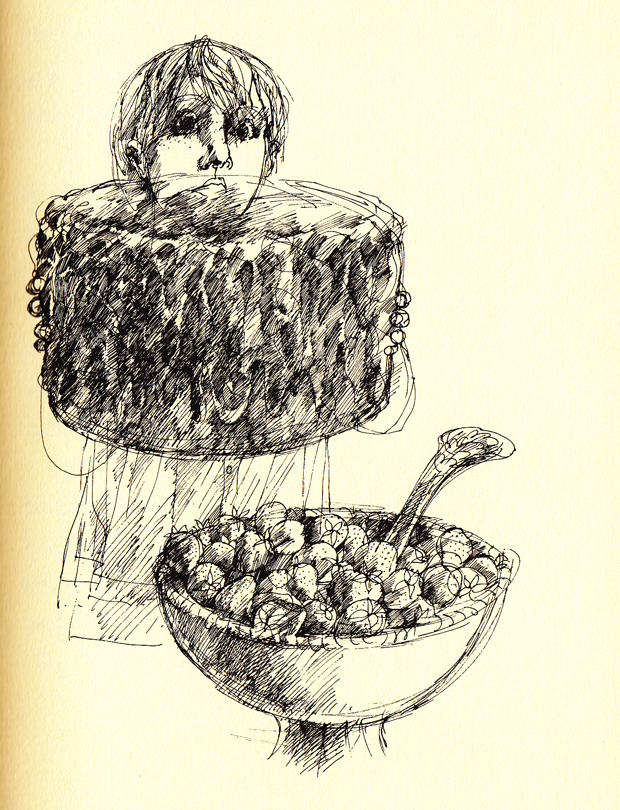

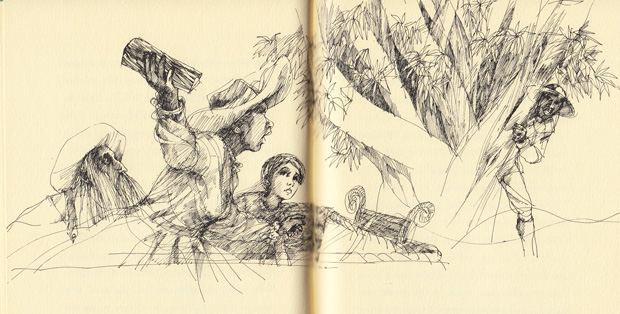

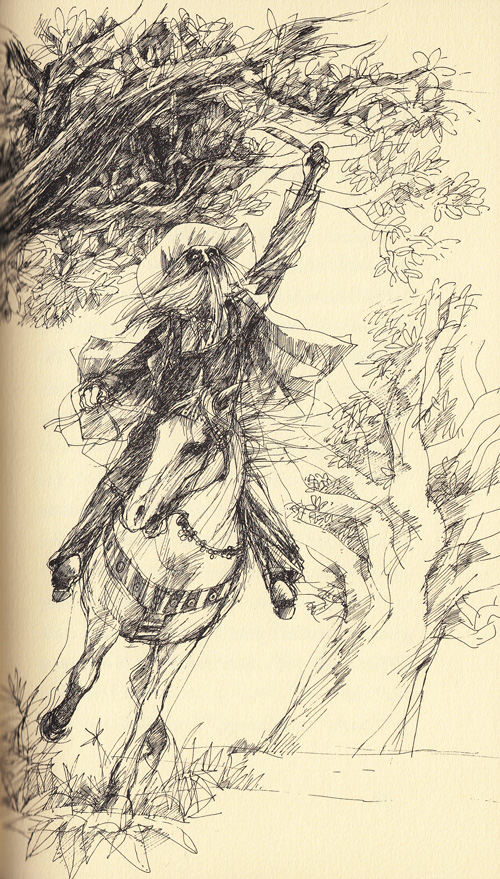

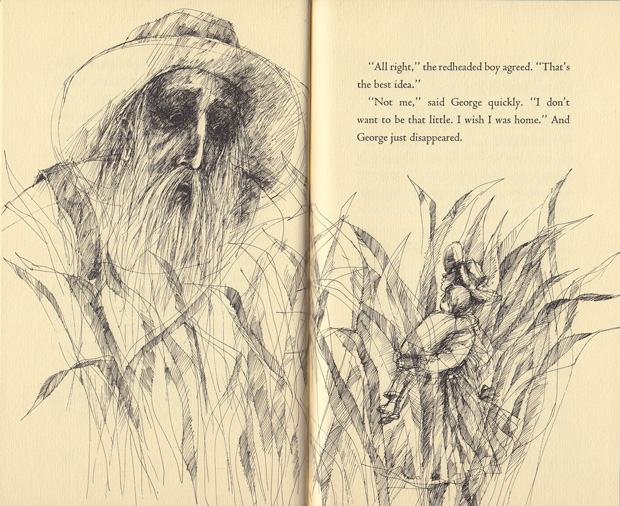

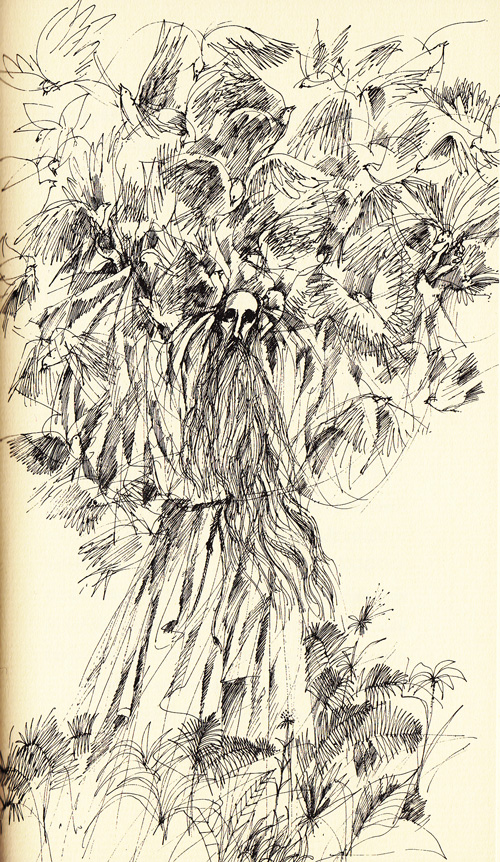

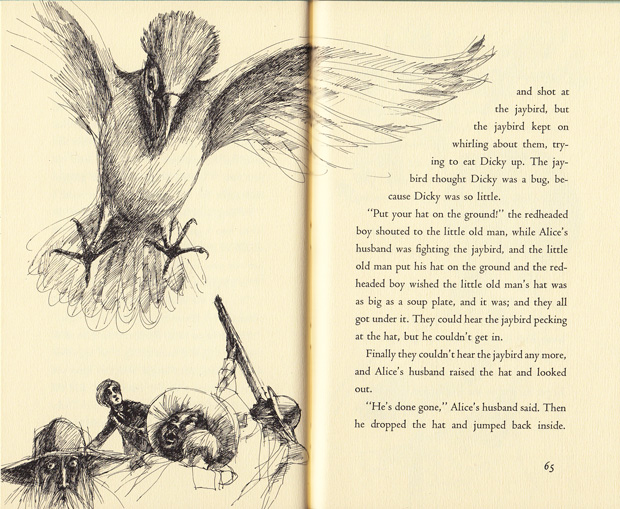

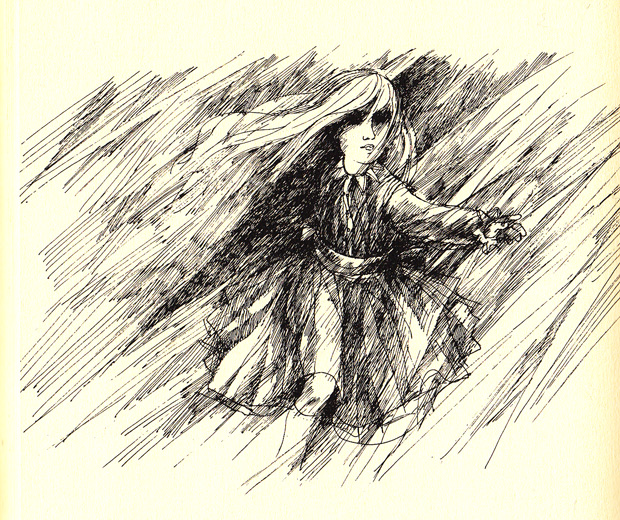

As a lover of obscure children’s books by famous authors of grown-up literature, I was delighted to discover The Wishing Tree (UK; public library) by none other than William Faulkner — a sort of grimly whimsical morality tale, somewhere between Alice In Wonderland, Don Quixote, and To Kill a Mockingbird, about a girl who embarks upon a strange adventure on her birthday only to realize the importance of choosing one’s wishes with consideration and kindness.

As a lover of obscure children’s books by famous authors of grown-up literature, I was delighted to discover The Wishing Tree (UK; public library) by none other than William Faulkner — a sort of grimly whimsical morality tale, somewhere between Alice In Wonderland, Don Quixote, and To Kill a Mockingbird, about a girl who embarks upon a strange adventure on her birthday only to realize the importance of choosing one’s wishes with consideration and kindness.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter and people say it’s cool. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter and people say it’s cool. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.